In this blog post, we explain two optimizations for WebAssembly that we recently implemented in V8 and that shipped with Google Chrome M137, namely speculative call_indirect inlining and deoptimization support for WebAssembly. In combination, they allow us to generate better machine code by making assumptions based on runtime feedback. This speeds up WebAssembly execution, in particular for WasmGC programs. On a set of Dart microbenchmarks for example, the speedup by the combination of both optimizations is more than 50% on average, and on larger, realistic applications and benchmarks shown below the speedup is between 1% and 8%. Deoptimizations are also an important building block for further optimizations in the future.

Background #

Fast execution of JavaScript relies heavily on speculative optimizations. That is, JIT-compilers make assumptions when generating machine code based on feedback that was collected during earlier executions. For example, given the expression a + b, the compiler can generate machine code for an integer addition if past feedback indicates that a and b are integers (and not strings, floating point numbers, or other objects). Without making such assumptions, the compiler would have to emit generic code that handles the full behavior of the + operator in JavaScript, which is complex and thus much slower. If the program later behaves differently and thus violates assumptions made when generating the optimized code, V8 performs a deoptimization (or deopt, for short). That means throwing away the optimized code and continuing execution in unoptimized code (and collecting more feedback to possibly tier-up again later).

In contrast to JavaScript, fast execution of WebAssembly hasn’t required speculative optimizations and deopts. One reason is that WebAssembly programs can already be optimized quite well because more information is statically available as e.g., functions, instructions, and variables are all statically typed. Another reason is that WebAssembly binaries are often compiled from C, C++, or Rust. These source languages are also more amenable to static analysis than JavaScript, and thus toolchains such as Emscripten (based on LLVM) or Binaryen can already optimize the program ahead-of-time. This results in fairly well-optimized binaries, at least when targeting WebAssembly 1.0, which launched in 2017.

Motivation #

Then why do we employ more speculative optimizations for WebAssembly in V8 now? One reason is that WebAssembly has evolved with the introduction of WasmGC, the WebAssembly Garbage Collection proposal. It better supports compiling “managed” languages such as Java, Kotlin, or Dart to WebAssembly. The resulting WasmGC bytecode is more high-level than Wasm 1.0, e.g., it supports rich types, such as structs and arrays, subtyping, and operations on such types. The generated machine code for WasmGC thus benefits more from speculative optimizations.

One particularly important optimization is inlining, that is, replacing a call instruction with the body of the callee function. Not only does this get rid of the administrative overhead associated with the call itself (which might be higher than the actual work for very small functions), but it also enables many other, subsequent optimizations to “see through” the function call, even if those optimizations are not inter-procedural. No wonder inlining was already recognized in 1971 as one of the most important optimizations in Frances Allen’s seminal “Catalogue of Optimizing Transformations”.

One complication for inlining are indirect calls, i.e., calls where the callee is only known at runtime and can be one of many potential targets. This is particularly true for the languages that compile to WasmGC. Consider Java or Kotlin where methods are virtual by default, whereas in C++ one has to opt-in by marking them explicitly. If there is not a single statically known callee, inlining is obviously not as straightforward.

Speculative Inlining #

This is where speculative inlining comes into play. In theory, indirect calls can target many different functions, but in practice, they still often go to a single target (called a monomorphic function call) or a few select cases (called polymorphic). We record those targets when executing the unoptimized code, and then inline up to four target functions when generating the optimized code. Speculative inlining overview

Speculative inlining overview

The figure above shows the high-level picture. We start at the top left, with the unoptimized code for function func_a, generated by Liftoff, our baseline compiler for WebAssembly. At each call site Liftoff also emits code to update the feedback vector. This metadata array exists once per function, and it contains one entry per call instruction in the given function. Each entry records the call targets and counts for this particular call site. The example feedback at the bottom of the figure shows a monomorphic entry for the call_indirect in func_a; here the call target was 1337 times func_b.

When a function is hot enough to tier-up to TurboFan, i.e., gets compiled with our optimizing compiler, we come to the second step. TurboFan reads the corresponding feedback vector and decides whether and which targets to inline at each call site. Whether it is worthwhile inlining one or multiple callees depends on a variety of heuristics. E.g., large functions are never inlined, tiny functions are almost always inlined, and generally there is a maximum inlining budget after which no more inlining into a function happens, as that also has costs in terms of compile time and generated machine code size. As in many places in compilers, particularly multi-tier JITs, these trade-offs are quite complex and get tuned over time. In this example, TurboFan decides to inline func_b into func_a.

On the upper right hand side of the figure, we see the result of speculative inlining in the generated optimized code. Instead of an indirect call, the code first checks if the target at runtime matches what we have assumed during compilation. If that’s the case, we continue executing the inlined body of the corresponding function. Subsequent optimizations can also transform the inlined code further, given the now available surrounding context. E.g., constant propagation and constant folding could specialize the code to this particular call site or GVN could hoist out repeated computations. In the case of polymorphic feedback, TurboFan can also emit a series of target checks and inlined bodies, not just one as in this example.

Technical Deep Dive #

So much for the high-level picture. For readers interested in the implementation, we look at some more details and concrete code in this section.

In the figure above, the feedback vector is only shown conceptually as an array of entries and only one kind of entry is shown. Below, we see that each entry can go through four stages over the course of the execution: Initially, all entries are uninitialized (all call counts are zero), potentially transitioning to monomorphic (a single call target was recorded), polymorphic (up to four call targets), and finally megamorphic (more than four targets, where we don’t inline any more and thus don’t need to record call counts either). Each entry is actually a pair of objects such that the most common monomorphic case can store both the call count and the target inline in the vector, i.e., without an additional allocation. For the polymorphic case, feedback is stored in an out-of-line array, as shown below. The builtin that updates a feedback entry (corresponding to update_feedback() in the first figure) is written in Torque. (It’s quite easy to read, give it a try!) It first checks for monomorphic or polymorphic “hits”, where just the count has to be incremented. This is again because they are the most common cases and thus performance-sensitive. The feedback vector and its entries are JavaScript objects (e.g., the call counts are Smis), so they live on the managed heap. As such, it is part of the V8 sandbox and is automatically cleaned up if the corresponding Wasm instance (see below) is no longer reachable. Details of the feedback vector

Details of the feedback vector

Next, let’s look at the effect of inlining on an actual WebAssembly program. The example function below does 200M indirect calls in a loop to a single target inlinee that contains an addition. Obviously, this is a somewhat simplified microbenchmark, but it demonstrates the benefits of speculative inlining well.

(func $example (param $iterations i32) (result i32)

(local $sum i32)

block $block

loop $loop

local.get $iterations

i32.eqz

br_if $block

local.get $iterations

i32.const 1

i32.sub

local.set $iterations

i32.const 7

i32.const 1

call_indirect (param i32) (result i32)

local.get $sum

i32.add

local.set $sum

br $loop

end

end

local.get $sum

)

...

(func $inlinee (param $x i32) (result i32)

local.get $x

i32.const 37

i32.add

)

For readers not familiar with the WebAssembly text format, here is a rough C equivalent of the above program:

int inlinee(int x) {

return x + 37;

}

int (*func_ptr)(int) = inlinee;

int example(int iterations) {

int sum = 0;

while (iterations != 0) {

iterations--;

sum += func_ptr(7);

}

return sum;

}

The next figure shows excerpts of TurboFan’s intermediate representation for the example function, visualized with Turbolizer: Speculative inlining and Wasm deopts are enabled on the right, and disabled on the left. In both versions, we have to check whether the table index argument to the call_indirect instruction is in-bounds, as per the WebAssembly semantics (first red box in both cases). Without inlining, we also have to check whether the function at this index has the correct signature before actually calling it (second red box on the left). Finally, the first green box on the left is the indirect call, and the second green box is the addition of the result of said call. In the green box on the right, we see that after inlining and further optimizations, the call is completely gone and the addition in inlinee and the addition in example were constant-folded into a single addition with a constant. Altogether, on this particular microbenchmark, inlining, deopts, and subsequent optimizations speed up the program from around 675 ms to 90 ms execution time on an x64 workstation. In this case, the optimized machine code with inlining is even smaller than without (968 vs. 1572 bytes), although that certainly need not be. TurboFan IR without and with inlining

TurboFan IR without and with inlining

Finally, we want to briefly explain the Wasm instance check and target check that the code with speculative inlining does on the right. Semantically, Wasm functions are closures over a Wasm instance (which “holds” the current state of globals, tables, imports from the host, etc.). Correctly inlining functions that belong to a different instance (e.g., which are called via an imported table) would hence require additional compiler machinery as well as solving a few obstacles in our general handling of generated code. Luckily, most calls are within a single instance anyway, so for the time being we check that the call target’s instance matches the current instance, which lets the compiler make the simplifying assumption that both instances are the same. If not, we deoptimize in block 8 (due to wrong instance) or block 6 (due to wrong target).

This additional Wasm instance check was specifically introduced for the new call_indirect inlining. WebAssembly also has another kind of indirect call, call_ref, for which we already added inlining support when launching our WasmGC implementation. The fast path for call_ref inlining doesn’t require an explicit instance check, since the WasmFuncRef object that is the call_ref input already includes the instance the function closes over, so comparing the target for equality subsumes both checks.

With the new call_indirect inlining, V8 now supports inlining Wasm-to-Wasm calls for all types of call instructions: direct calls, call_ref, call_indirect, and their respective tail-call variants return_call, return_call_ref, and return_call_indirect.

Deoptimization #

So far, we have focused on inlining and how that improves the optimized code. But what happens if we cannot stay on a fast path, i.e., if one of the assumptions made during optimization turns out to be false at runtime? This is where deopts come into play.

The very first figure of this post already shows the high-level idea of a deopt: We cannot continue execution in the optimized code because it has made some assumptions that are now invalidated. So instead, we “go back” to the unoptimized baseline code. Crucially, this transition to unoptimized code happens in the middle of executing the current function, i.e., when the optimized code has already performed operations with side-effects (say, called the underlying operating system), which we cannot undo, and while it is holding intermediate values in registers and on the stack. So a deopt cannot just jump to the beginning of the unoptimized function, but instead does something much more interesting:

First, we save the current program state. We do this by calling into the runtime from optimized code. The Deoptimizer then serializes the current program state into an internal data structure, the FrameDescription. This entails reading out CPU registers and inspecting the stack frame of the function to be deoptimized.

Next, we transform this state such that it fits the unoptimized code, that is, placing values in the correct registers and stack slots that the Liftoff-generated code expects at the deoptimization point. E.g., a value that TurboFan code has put in a register may now end up in a stack slot. The stack layout and expectations for the baseline code (its “calling convention” for the deopt point, if you will) are read out of metadata generated by Liftoff during compilation.

And finally, we replace the optimized stack frame with the corresponding unoptimized stack frame(s) and jump to the middle of the baseline code, corresponding to the point in the optimized code where the deopt was triggered.

Obviously, this is quite complex machinery, which begs the question: Why do we go through the hassle of it all and not just generate a slow path in optimized code? Let’s compare the intermediate representation for the earlier example WebAssembly code, left without and right with deopts. The three red boxes (table bounds / Wasm instance / target check) are fundamentally the same. The difference is in the code for the slow path. Without deopts, we don’t have the option of returning to baseline code, so the optimized code must handle the full, generic behavior of an indirect call, as shown in the yellow box on the left. This unfortunately impedes further optimizations and thus results in slower execution. TurboFan IR without and with deopts

TurboFan IR without and with deopts

There are two reasons why the non-deopt slow path impedes optimizations. First, it contains more operations, in particular a call, which we have to assume goes anywhere and has arbitrary side-effects. Second, note how the Deoptimize operation in block 8 on the right has no successor in the control-flow graph, whereas the yellow slow path on the left has a successor. In particular for loops, the deoptimization node/block will not produce data-flow facts (in the sense of data-flow analyses and optimizations, such as live variables, load elimination, or escape analysis) that propagate to the next iteration of the loop. In essence, the deopt point “just” terminates the execution of the function, without much effect on the surrounding code, which can be utilized nicely by subsequent optimizations.

Finally, this also explains why the combination of speculative optimizations (e.g., inlining) and deoptimization is so useful: The first adds a fast path based on speculative assumptions, and deopts allow the compiler to not worry much about the cases where the assumptions turn out to be false. Concretely, for the earlier microbenchmark with 200M indirect calls, performing just speculative inlining without deopts speeds up the program “only” to about 180 ms, compared to 90 ms with both inlining and deopts (and 675 ms without either).

Technical Deep Dive #

For the interested reader, we now again look at a concrete example and technical details, this time for when we deopt.

Let's assume we execute the optimized code from above but the function stored at table index 1 has changed in the meantime. The table bounds check and Wasm instance check will pass, but the inlined target will be different from the one in the table, so we need to deoptimize the program in its current state. For that the code contains so-called deoptimization exits. The target check conditionally jumps to such an exit, which itself is a call to the DeoptimizationEntry builtin. The builtin first saves all register values by spilling them to the stack. Then it allocates the C++ Deoptimizer object and its FrameDescription input object. The builtin copies the spilled registers and all other stack slots from the optimized frame into the FrameDescription on the heap, and pops these values from the stack in the process. (Note that the execution is still in the builtin while it has already removed its own return address from the stack and started unwinding the calling frame!) Then the builtin computes the output frames. To do that, the deoptimizer loads the DeoptimizationData for the optimized frame, extracts the information for the deopt point, and recompiles each inlined function at this call site with Liftoff. Due to nested inlining there can be more than one inlined function, and with inlined tail calls the optimized function to which the optimized stack frame nominally belonged might not even be part of the unoptimized stack frames to be constructed.

While compiling, Liftoff calculates the expected stack frame layout and the deoptimizer transforms the optimized frame description into the desired layouts reported by Liftoff. It returns to the builtin which then reads these output FrameDescription objects and pushes their values onto the stack. Finally the builtin fills in the registers from the top output FrameDescription.

For the example above, our internal tracing with --trace-deopt-verbose shows the following:

[bailout (kind: deopt-eager, reason: wrong call target, type: Wasm): begin. deoptimizing example, function index 2, bytecode offset 134, deopt exit 0, FP to SP delta 32, pc 0x14886e50cbb4]

reading input for Liftoff frame => bailout_id=134, height=4, function_id=2 ; inputs:

0: 4 ; rdx (int32)

1: 0 ; rbx (int32)

2: (wasm int32 literal 7)

3: (wasm int32 literal 1)

Liftoff stack & register state for function index 2, frame size 48, total frame size 64

0: i32:rax

1: i32:s0x28

2: i32:c7

3: i32:c1

[bailout end. took 0.082 ms]

First we can see that a deopt is triggered because of a wrong call target in Wasm for the function example. The trace then shows information about the input (optimized) frame, which has four values: The iterations parameter of the function (value 4, stored in register rdx), the sum local (0 stored in rbx), the literal 7 and the literal 1, which are the two arguments to the call_indirect instruction. In this simple example, there is only one unoptimized output frame, so there is a 1:1 mapping between the two frames: The iterations value has to be stored in register rax while the sum value needs to end up in the stack slot s0x28. The two constants are also recognized by Liftoff as constants and don’t need to be transferred into stack slots or registers.

After these transformations have been done the builtin “returns” to the inner-most unoptimized frame which calls a final builtin to clean-up the Deoptimizer object and perform any needed allocations on the managed heap. Finally, execution continues in the unoptimized code, in this case executing the call_indirect, which will also directly record the new call target in its feedback vector, so that any later tier-up is aware of this new target.

Results #

Besides the technical description and examples, we also want to demonstrate the usefulness of call_indirect inlining and Wasm deopt support with some measurements.

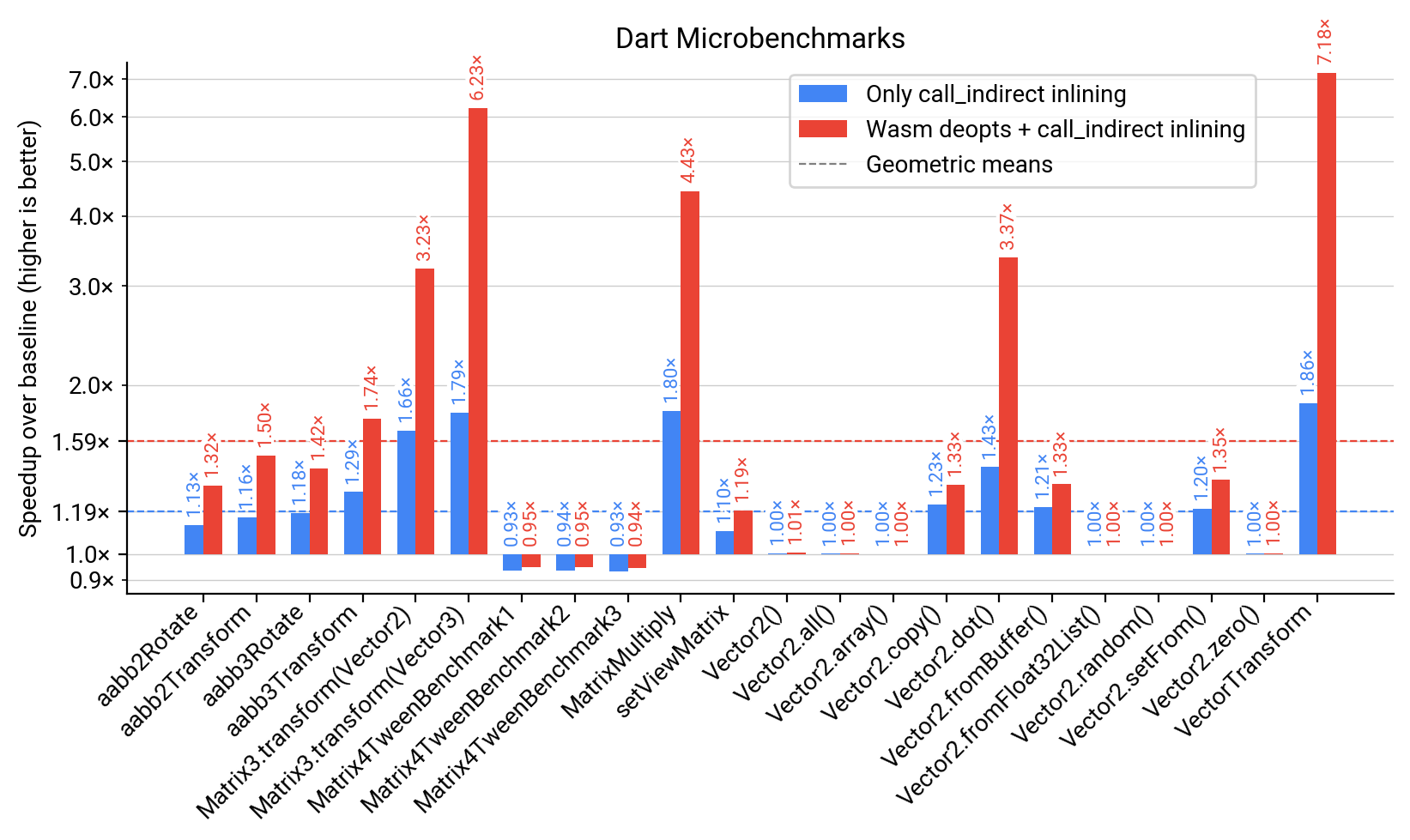

We first look at a collection of Dart microbenchmarks in the figure below. It compares three configurations against each other: All given numbers are speedups relative to V8 and Chrome’s behavior before call_indirect inlining and Wasm deopts (i.e., a speedup of 2x means the runtime is half of that of the baseline). The blue bars show the configuration with call_indirect inlining enabled but no Wasm deopts, i.e., where the optimized code contains a generic slow path. On several of these microbenchmarks this already yields (sometimes substantial) speedups. On average across all items, call_indirect inlining speeds up execution by 1.19x compared to the baseline without. Finally, the red bars show the configuration we actually ship, where both Wasm deopts and call_indirect inlining are enabled. With an average speedup of 1.59x over the baseline, this shows that in particular the combination of speculative optimizations and deoptimization support is highly beneficial.

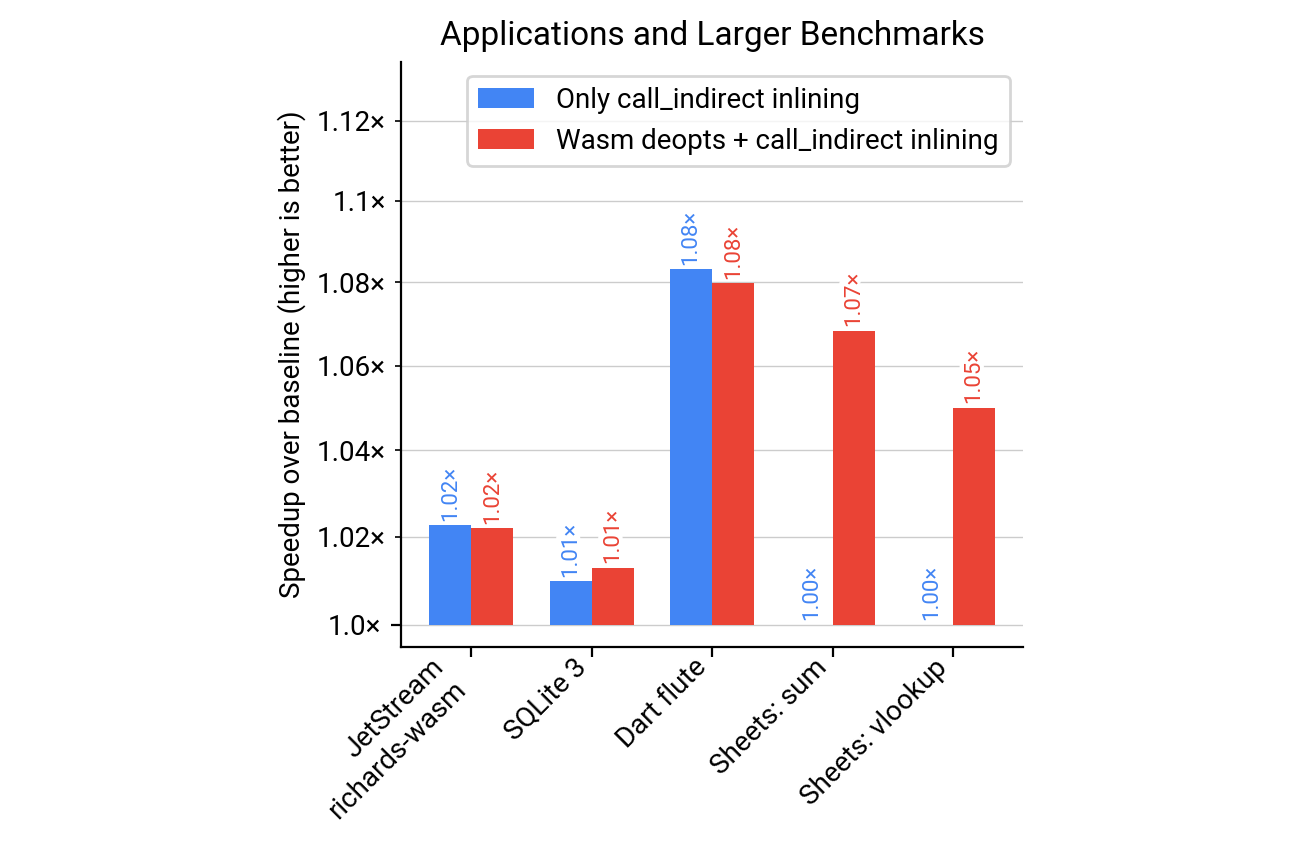

Naturally, microbenchmarks isolate and emphasize the effects of an optimization quite a bit. This is useful during development or to get a strong signal with noisy measurements. However, more realistic are results on larger applications and benchmarks, as shown in the following figure. To the very left, we see a 2% speedup in terms of runtime for richards-wasm, a workload from the JetStream benchmark suite. Next, we see a 1% speedup for a Wasm build of the widely-used SQLite 3 database, and 8% speedup for Dart Flute, a WasmGC benchmark that emulates a UI workload similar to Flutter. The final two results are from an internal benchmark for the Google Sheets calc engine, which is powered by WasmGC, with speedups due to deopts of up to 7% (only deopts matter here as this last application only uses call_refs for runtime dispatch, i.e., it has no call_indirects).

Conclusion and Outlook #

This concludes our post about two new optimizations in the V8 engine for WebAssembly. To summarize, we have seen:

- How speculative inlining can inline functions even in the presence of indirect calls,

- what feedback is and how it is used and updated,

- what to do when assumptions made during optimizations are invalid at runtime,

- how a deoptimization can exit optimized code and enters baseline code in the middle of executing a function, and finally

- how this significantly improves the execution of real-world workloads.

In the future, we plan on adding more speculative optimizations based on deopt support for WebAssembly, e.g. bounds-check elimination or more extensive load elimination for WasmGC objects. And also in terms of inlining, there is more to be done: While we now have Wasm-into-Wasm inlining for all kinds of call instructions, we can still extend inlining across the language boundary, e.g., for JavaScript-to-Wasm calls. Check back on our V8 blog for exciting updates in the future!