Roughly three months ago, I joined the V8 team (Google Munich) as an intern and since then I’ve been working on the VM’s Deoptimizer — something completely new to me which proved to be an interesting and challenging project. The first part of my internship focused on improving the VM security-wise. The second part focused on performance improvements. Namely, on the removal of a data-structure used for the unlinking of previously deoptimized functions, which was a performance bottleneck during garbage collection. This blog post describes this second part of my internship. I’ll explain how V8 used to unlink deoptimized functions, how we changed this, and what performance improvements were obtained.

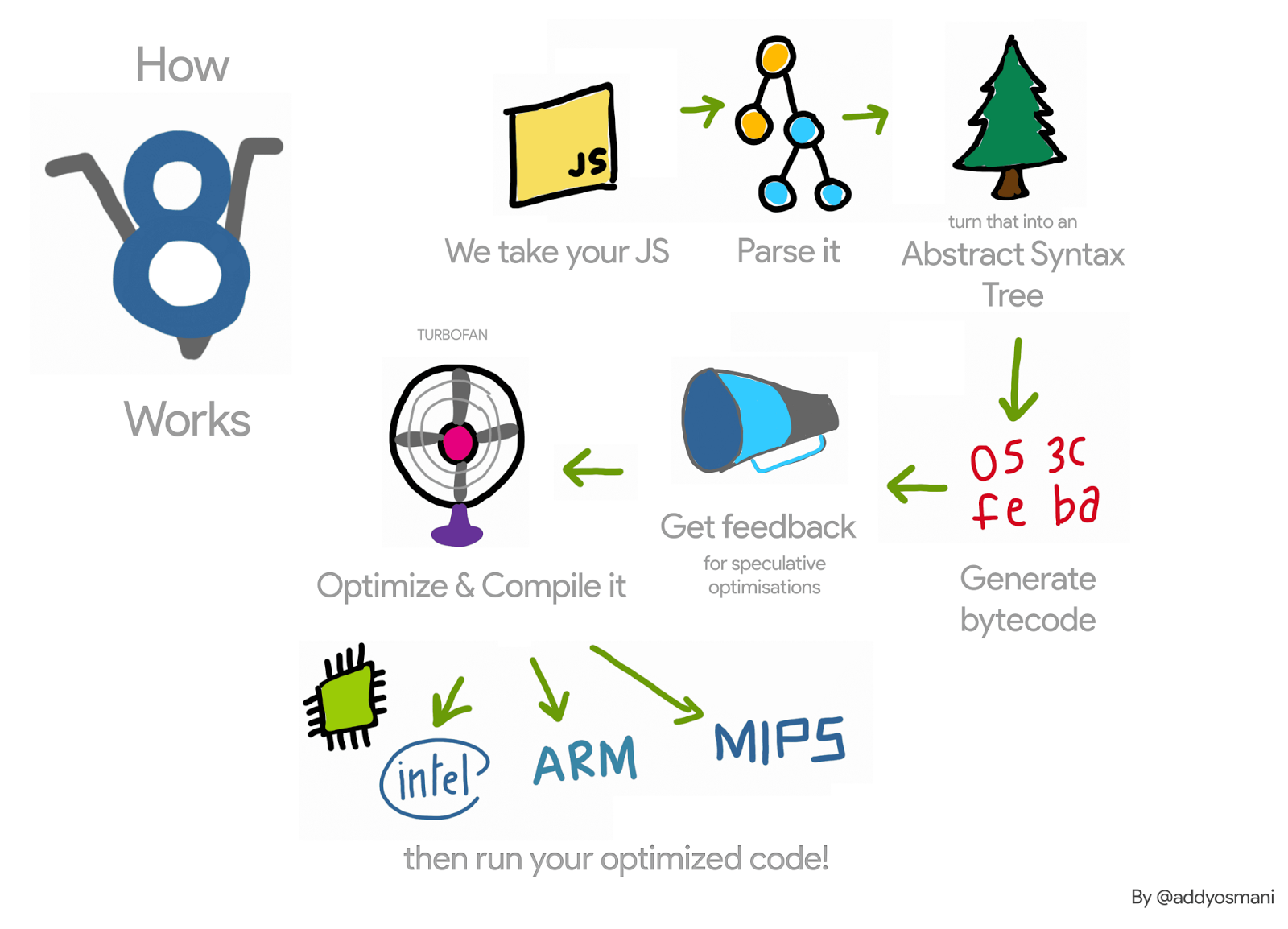

Let’s (very) briefly recap the V8 pipeline for a JavaScript function: V8’s interpreter, Ignition, collects profiling information about that function while interpreting it. Once the function becomes hot, this information is passed to V8’s compiler, TurboFan, which generates optimized machine code. When the profiling information is no longer valid — for example because one of the profiled objects gets a different type during runtime — the optimized machine code might become invalid. In that case, V8 needs to deoptimize it. An overview of V8, as seen in JavaScript Start-up Performance

An overview of V8, as seen in JavaScript Start-up Performance

Upon optimization, TurboFan generates a code object, i.e. the optimized machine code, for the function under optimization. When this function is invoked the next time, V8 follows the link to optimized code for that function and executes it. Upon deoptimization of this function, we need to unlink the code object in order to make sure that it won’t be executed again. How does that happen?

For example, in the following code, the function f1 will be invoked many times (always passing an integer as argument). TurboFan then generates machine code for that specific case.

function g() {

return (i) => i;

}

const f1 = g();

for (var i = 0; i < 1000; i++) f1(0);

Each function also has a trampoline to the interpreter — more details in these slides — and will keep a pointer to this trampoline in its SharedFunctionInfo (SFI). This trampoline will be used whenever V8 needs to go back to unoptimized code. Thus, upon deoptimization, triggered by passing an argument of a different type, for example, the Deoptimizer can simply set the code field of the JavaScript function to this trampoline. An overview of V8, as seen in JavaScript Start-up Performance

An overview of V8, as seen in JavaScript Start-up Performance

Although this seems simple, it forces V8 to keep weak lists of optimized JavaScript functions. This is because it is possible to have different functions pointing to the same optimized code object. We can extend our example as follows, and the functions f1 and f2 both point to the same optimized code.

const f2 = g();

f2(0);

If the function f1 is deoptimized (for example by invoking it with an object of different type {x: 0}) we need to make sure that the invalidated code will not be executed again by invoking f2.

Thus, upon deoptimization, V8 used to iterate over all the optimized JavaScript functions, and would unlink those that pointed to the code object being deoptimized. This iteration in applications with many optimized JavaScript functions became a performance bottleneck. Moreover, other than slowing down deoptimization, V8 used to iterate over these lists upon stop-the-world cycles of garbage collection, making it even worse.

In order to have an idea of the impact of such data-structure in the performance of V8, we wrote a micro-benchmark that stresses its usage, by triggering many scavenge cycles after creating many JavaScript functions.

function g() {

return (i) => i + 1;

}

var f = g();

f(0);

f(0);

%OptimizeFunctionOnNextCall(f);

f(0);

var a = [];

for (var i = 0; i < 2000000; i++) {

var h = g();

h();

a.push(h);

}

for (var i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

new Array(50000);

}

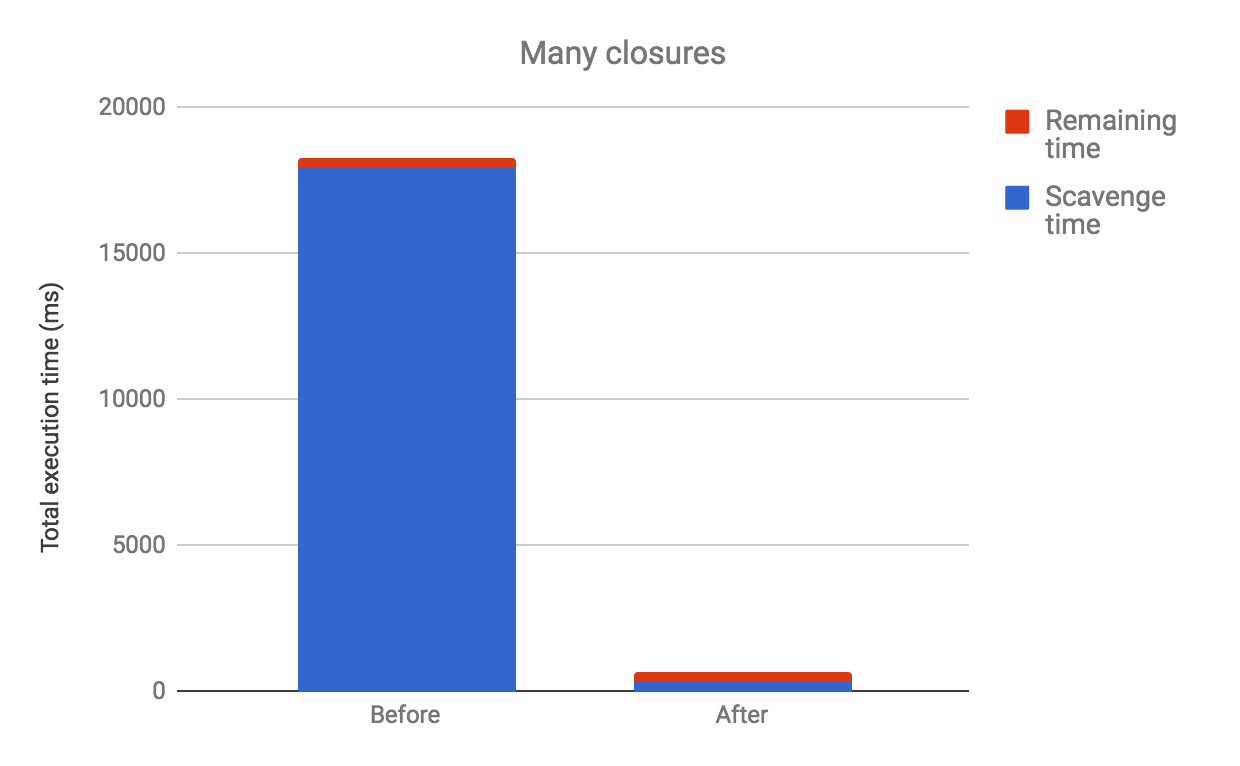

When running this benchmark, we could observe that V8 spent around 98% of its execution time on garbage collection. We then removed this data structure, and instead used an approach for lazy unlinking, and this was what we observed on x64:

Although this is just a micro-benchmark that creates many JavaScript functions and triggers many garbage collection cycles, it gives us an idea of the overhead introduced by this data structure. Other more realistic applications where we saw some overhead, and which motivated this work, were the router benchmark implemented in Node.js and ARES-6 benchmark suite.

Lazy unlinking #

Rather than unlinking optimized code from JavaScript functions upon deoptimization, V8 postpones it for the next invocation of such functions. When such functions are invoked, V8 checks whether they have been deoptimized, unlinks them and then continues with their lazy compilation. If these functions are never invoked again, then they will never be unlinked and the deoptimized code objects will not be collected. However, given that during deoptimization, we invalidate all the embedded fields of the code object, we only keep that code object alive.

The commit that removed this list of optimized JavaScript functions required changes in several parts of the VM, but the basic idea is as follows. When assembling the optimized code object, we check if this is the code of a JavaScript function. If so, in its prologue, we assemble machine code to bail out if the code object has been deoptimized. Upon deoptimization we don’t modify the deoptimized code — code patching is gone. Thus, its bit marked_for_deoptimization is still set when invoking the function again. TurboFan generates code to check it, and if it is set, then V8 jumps to a new builtin, CompileLazyDeoptimizedCode, that unlinks the deoptimized code from the JavaScript function and then continues with lazy compilation.

In more detail, the first step is to generate instructions that load the address of the code being currently assembled. We can do that in x64, with the following code:

Label current;

__ leaq(rcx, Operand(¤t));

__ bind(¤t);

After that we need to obtain where in the code object the marked_for_deoptimization bit lives.

int pc = __ pc_offset();

int offset = Code::kKindSpecificFlags1Offset - (Code::kHeaderSize + pc);

We can then test the bit and if it is set, we jump to the CompileLazyDeoptimizedCode built in.

__ testl(Operand(rcx, offset),

Immediate(1 << Code::kMarkedForDeoptimizationBit));

__ j(not_zero, , RelocInfo::CODE_TARGET);

On the side of this CompileLazyDeoptimizedCode builtin, all that’s left to do is to unlink the code field from the JavaScript function and set it to the trampoline to the Interpreter entry. So, considering that the address of the JavaScript function is in the register rdi, we can obtain the pointer to the SharedFunctionInfo with:

__ movq(rcx, FieldOperand(rdi, JSFunction::kSharedFunctionInfoOffset));

…and similarly the trampoline with:

__ movq(rcx, FieldOperand(rcx, SharedFunctionInfo::kCodeOffset));

Then we can use it to update the function slot for the code pointer:

__ movq(FieldOperand(rdi, JSFunction::kCodeOffset), rcx);

__ RecordWriteField(rdi, JSFunction::kCodeOffset, rcx, r15,

kDontSaveFPRegs, OMIT_REMEMBERED_SET, OMIT_SMI_CHECK);

This produces the same result as before. However, rather than taking care of the unlinking in the Deoptimizer, we need to worry about it during code generation. Hence the handwritten assembly.

The above is how it works in the x64 architecture. We have implemented it for ia32, arm, arm64, mips, and mips64 as well.

This new technique is already integrated in V8 and, as we’ll discuss later, allows for performance improvements. However, it comes with a minor disadvantage: Before, V8 would consider unlinking only upon deoptimization. Now, it has to do so in the activation of all optimized functions. Moreover, the approach to check the marked_for_deoptimization bit is not as efficient as it could be, given that we need to do some work to obtain the address of the code object. Note that this happens when entering every optimized function. A possible solution for this issue is to keep in a code object a pointer to itself. Rather than doing work to find the address of the code object whenever the function is invoked, V8 would do it only once, after its construction.

Results #

We now look at the performance gains and regressions obtained with this project.

General improvements on x64 #

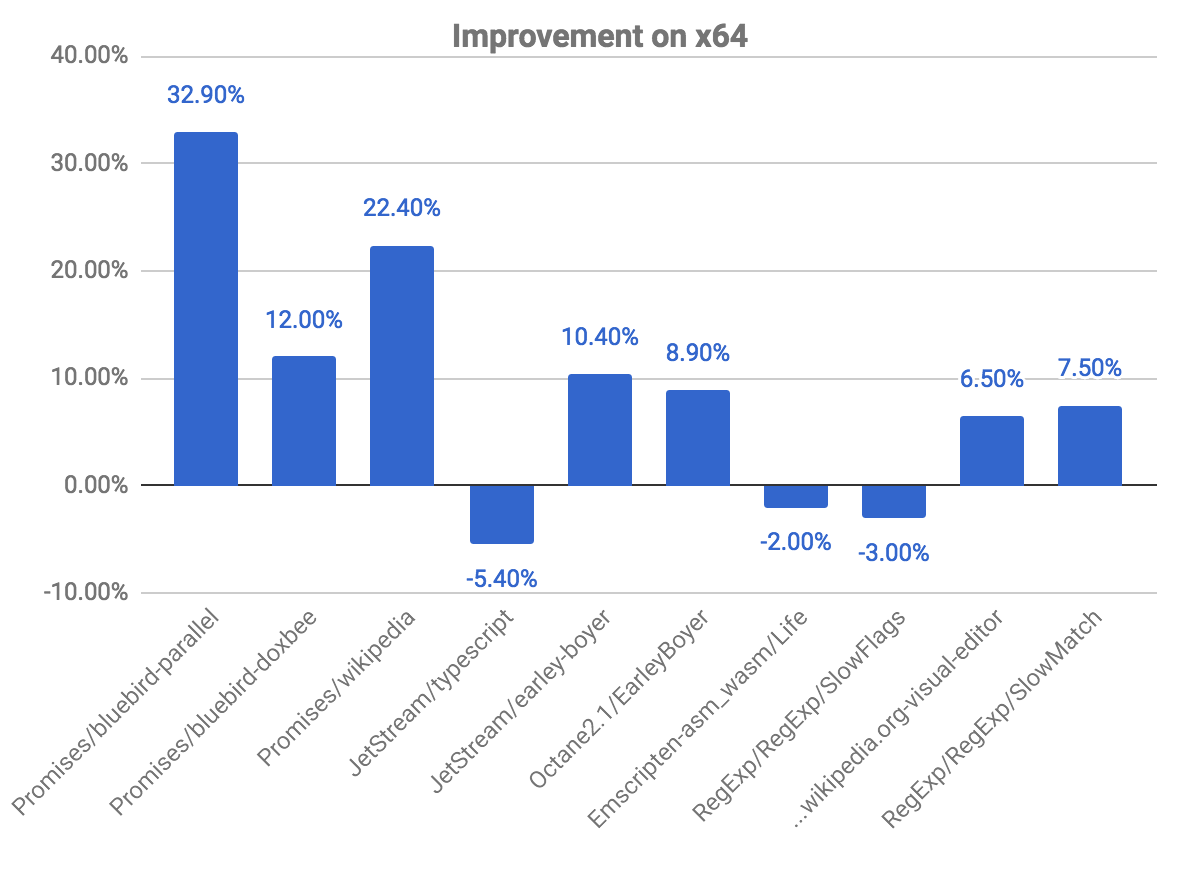

The following plot shows us some improvements and regressions, relative to the previous commit. Note that the higher, the better.

The promises benchmarks are the ones where we see greater improvements, observing almost 33% gain for the bluebird-parallel benchmark, and 22.40% for wikipedia. We also observed a few regressions in some benchmarks. This is related to the issue explained above, on checking whether the code is marked for deoptimization.

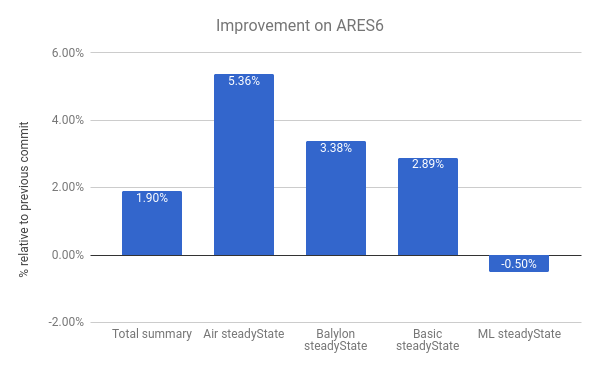

We also see improvements in the ARES-6 benchmark suite. Note that in this chart too, the higher the better. These programs used to spend considerable amount of time in GC-related activities. With lazy unlinking we improve performance by 1.9% overall. The most notable case is the Air steadyState where we get an improvement of around 5.36%.

AreWeFastYet results #

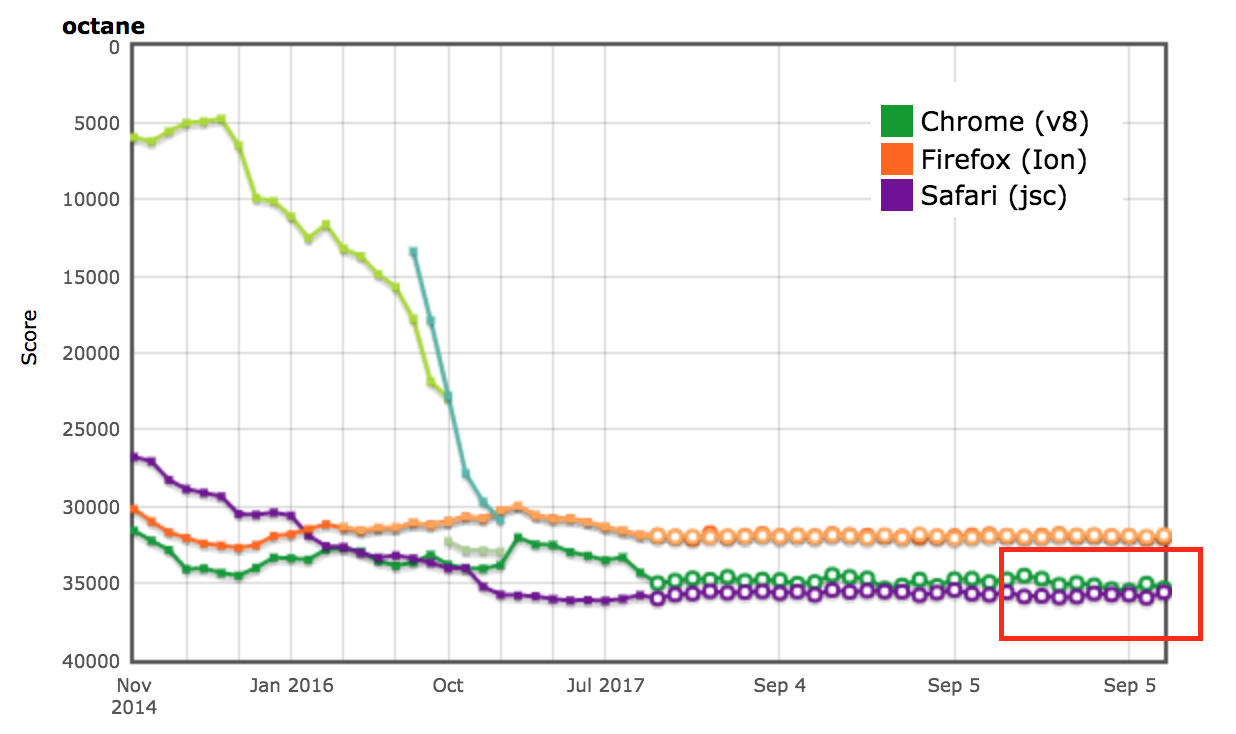

The performance results for the Octane and ARES-6 benchmark suites also showed up on the AreWeFastYet tracker. We looked at these performance results on September 5th, 2017, using the provided default machine (macOS 10.10 64-bit, Mac Pro, shell). Cross-browser results on Octane as seen on AreWeFastYet

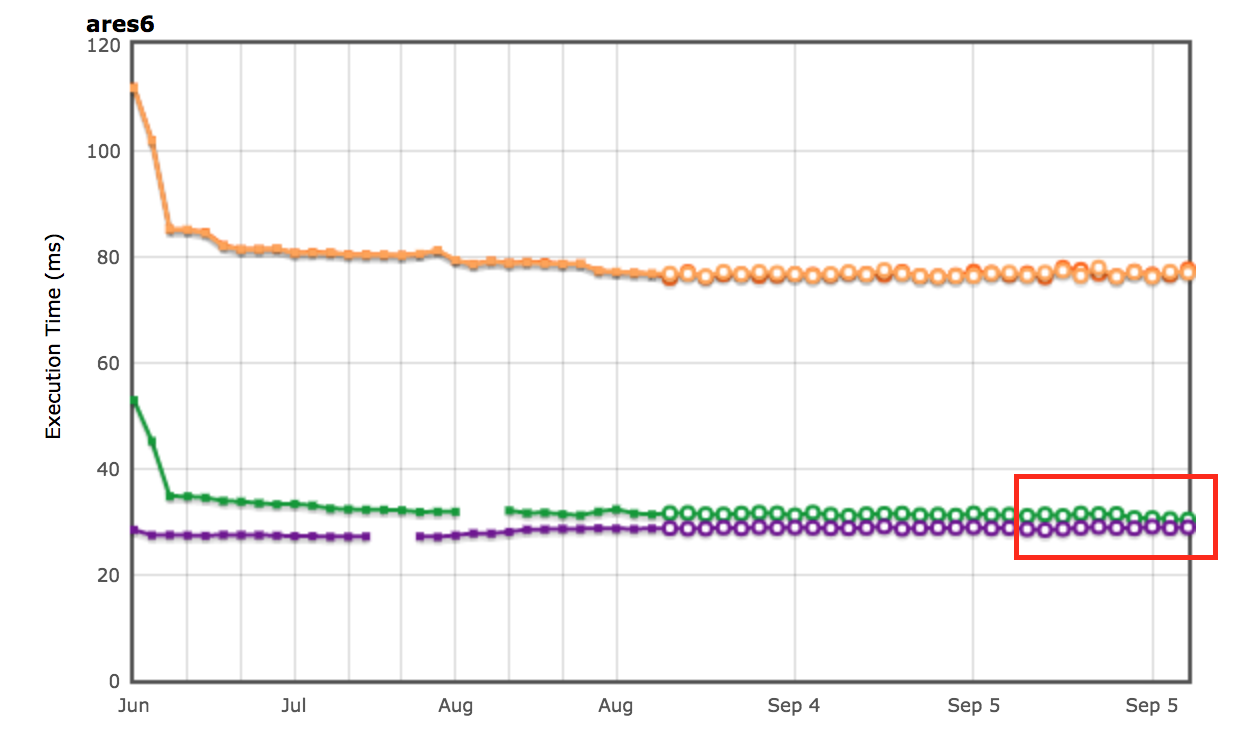

Cross-browser results on Octane as seen on AreWeFastYet Cross-browser results on ARES-6 as seen on AreWeFastYet

Cross-browser results on ARES-6 as seen on AreWeFastYet

Impact on Node.js #

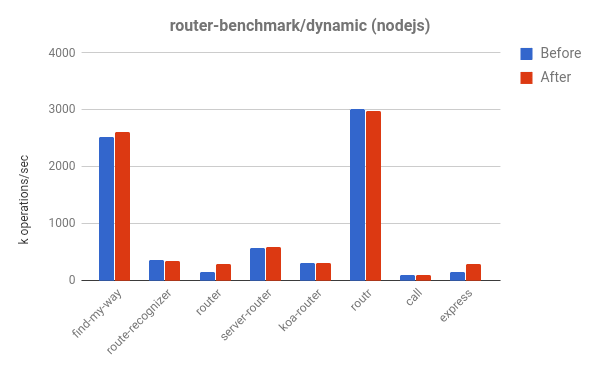

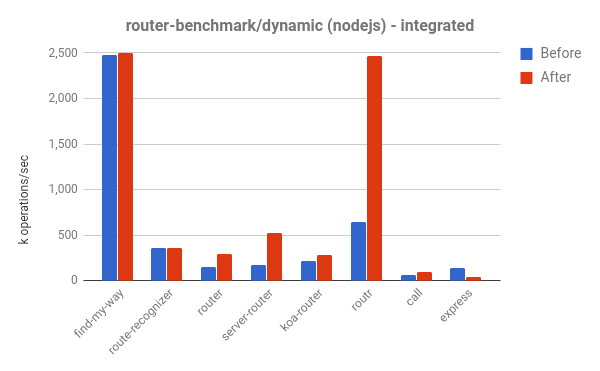

We can also see performance improvements in the router-benchmark. The following two plots show the number of operations per second of each tested router. Thus the higher the better. We have performed two kinds of experiments with this benchmark suite. Firstly, we ran each test in isolation, so that we could see the performance improvement, independently from the remaining tests. Secondly, we ran all tests at once, without switching of the VM, thus simulating an environment where each test is integrated with other functionalities.

For the first experiment, we saw that the router and express tests perform about twice as many operations than before, in the same amount of time. For the second experiment, we saw even greater improvement. In some of the cases, such as routr, server-router and router, the benchmark performs approximately 3.80×, 3× and 2× more operations, respectively. This happens because V8 accumulates more optimized JavaScript functions, test after test. Thus, whenever executing a given test, if a garbage collection cycle is triggered, V8 has to visit the optimized functions from the current test and from the previous ones.

Further optimization #

Now that V8 does not keep the linked-list of JavaScript functions in the context, we can remove the field next from the JSFunction class. Although this is a simple modification, it allows us to save the size of a pointer per function, which represent significant savings in several web pages:

| Benchmark | Kind | Memory savings (absolute) | Memory savings (relative) |

|---|

| facebook.com | Average effective size | 170 KB | 3.70% |

| twitter.com | Average size of allocated objects | 284 KB | 1.20% |

| cnn.com | Average size of allocated objects | 788 KB | 1.53% |

| youtube.com | Average size of allocated objects | 129 KB | 0.79% |

Acknowledgments #

Throughout my internship, I had lots of help from several people, who were always available to answer my many questions. Thus I would like to thank the following people: Benedikt Meurer, Jaroslav Sevcik, and Michael Starzinger for discussions on how the compiler and the deoptimizer work, Ulan Degenbaev for helping with the garbage collector whenever I broke it, and Mathias Bynens, Peter Marshall, Camillo Bruni, and Maya Armyanova for proofreading this article.

Finally, this article is my last contribution as a Google intern and I would like to take the opportunity to thank everyone in the V8 team, and especially my host, Benedikt Meurer, for hosting me and for giving me the opportunity to work on such an interesting project — I definitely learned a lot and enjoyed my time at Google!