V8 uses code caching to cache the generated code for frequently-used scripts. Starting with Chrome 66, we are caching more code by generating the cache after top-level execution. This leads to a 20–40% reduction in parse and compilation time during the initial load.

Background #

V8 uses two kinds of code caching to cache generated code to be reused later. The first is the in-memory cache that is available within each instance of V8. The code generated after the initial compile is stored into this cache, keyed on the source string. This is available for reuse within the same instance of V8. The other kind of code caching serializes the generated code and stores it on disk for future use. This cache is not specific to a particular instance of V8 and can be used across different instances of V8. This blog post focuses on this second kind of code caching as used in Chrome. (Other embedders also use this kind of code caching; it’s not limited to Chrome. However, this blog post only focuses on the usage in Chrome.)

Chrome stores the serialized generated code onto the disk cache and keys it with the URL of the script resource. When loading a script, Chrome checks the disk cache. If the script is already cached, Chrome passes the serialized data to V8 as a part of compile request. V8 then deserializes this data instead of parsing and compiling the script. There are also additional checks involved to ensure that the code is still usable (for example: a version mismatch makes the cached data unusable).

Real-world data shows that the code cache hit rates (for scripts that could be cached) is high (~86%). Though the cache hit rates are high for these scripts, the amount of code we cache per script is not very high. Our analysis showed that increasing the amount of code that is cached would reduce the time spent in parsing and compiling JavaScript code by around 40%.

Increasing the amount of code that is cached #

In the previous approach, code caching was coupled with the requests to compile the script.

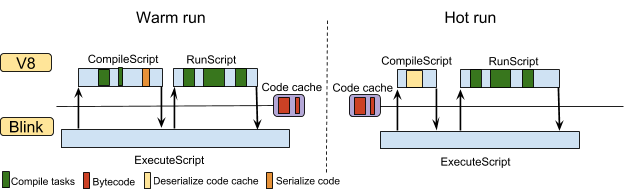

Embedders could request that V8 serialize the code it generated during its top-level compilation of a new JavaScript source file. V8 returned the serialized code after compiling the script. When Chrome requests the same script again, V8 fetches the serialized code from the cache and deserializes it. V8 completely avoids recompiling functions that are already in the cache. These scenarios are shown in the following figure:

V8 only compiles the functions that are expected to be immediately executed (IIFEs) during the top-level compile and marks other functions for lazy compilation. This helps improve page load times by avoiding compiling functions that are not required, however it means that the serialized data only contains the code for the functions that are eagerly compiled.

Prior to Chrome 59, we had to generate the code cache before any execution has started. The earlier baseline compiler of V8 (Full-codegen) generates specialized code for the execution context. Full-codegen used code patching to fast-path operations for the specific execution context. Such code cannot be serialized easily by removing the context specific data to be used in other execution contexts.

With the launch of Ignition in Chrome 59, this restriction is no longer necessary. Ignition uses data-driven inline caches to fast-path operations in the current execution context. The context-dependent data is stored in feedback vectors and is separate from the generated code. This has opened the possibility of generating code caches even after the execution of the script. As we execute the script, more functions (that were marked for lazy compile) are compiled, allowing us to cache more code.

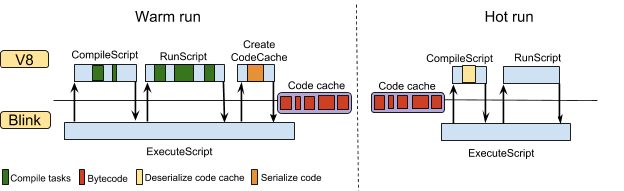

V8 exposes a new API, ScriptCompiler::CreateCodeCache, to request code caches independent of the compile requests. Requesting code caches along with compile requests is deprecated and would not work in V8 v6.6 onwards. Since version 66, Chrome uses this API to request the code cache after the top-level execute. The following figure shows the new scenario of requesting the code cache. The code cache is requested after the top level execute and hence contains the code for functions that were compiled later during the execution of the script. In the later runs (shown as hot runs in the following figure), it avoids compilation of functions during top level execute.

Results #

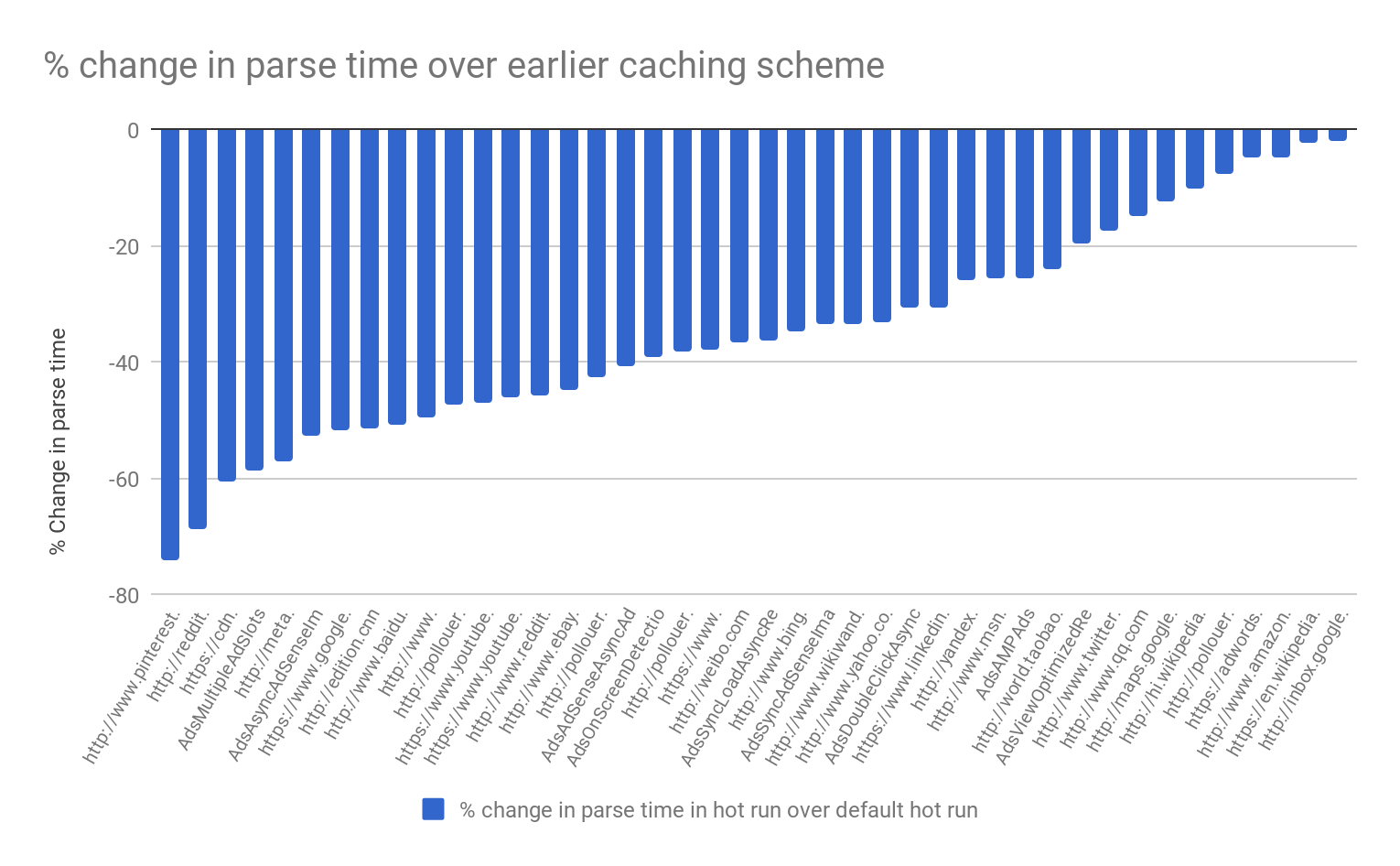

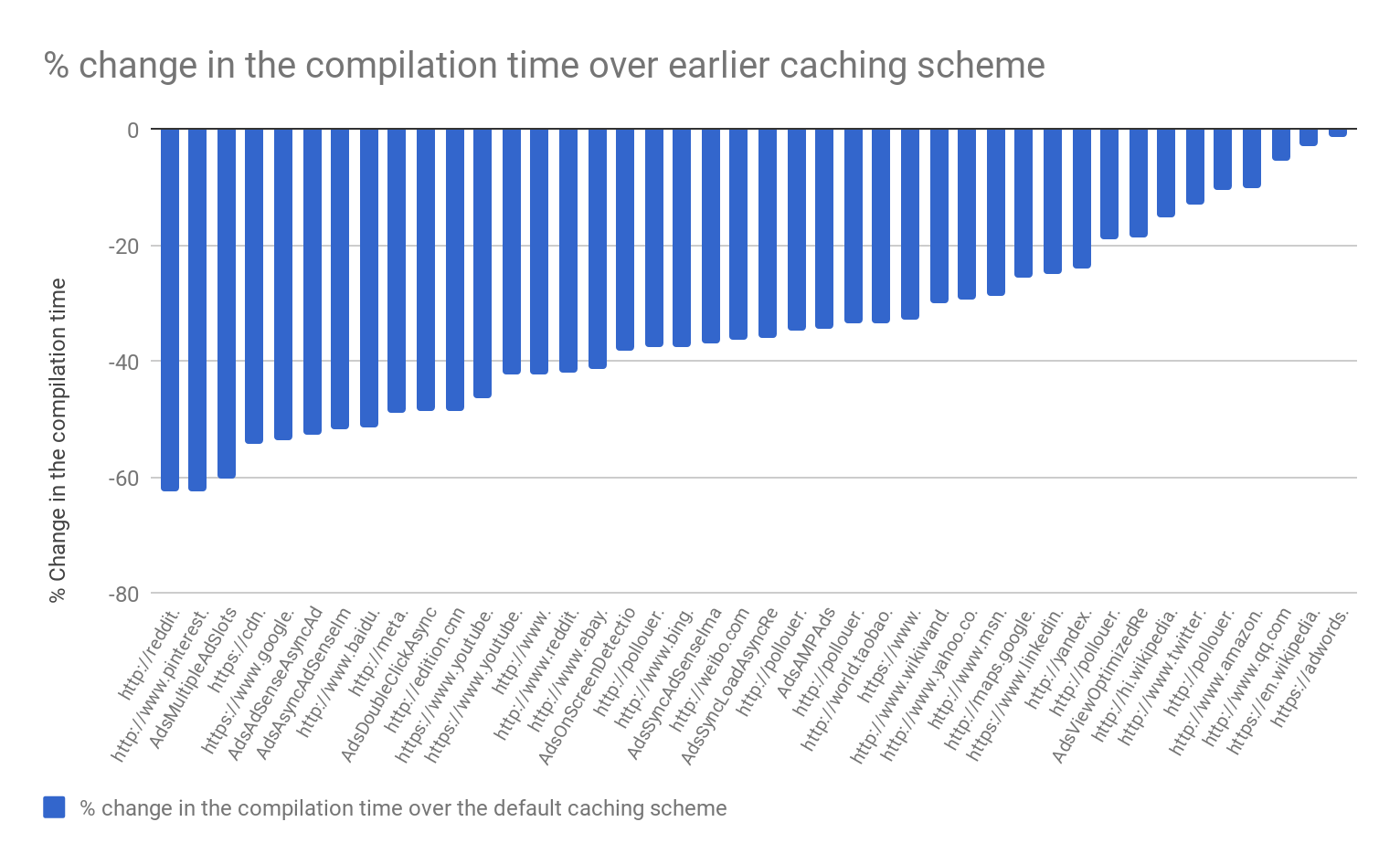

The performance of this feature is measured using our internal real-world benchmarks. The following graph shows the reduction in the parse and compile time over the earlier caching scheme. There is a reduction of around 20–40% in both parse and compilation time on most of the pages.

Data from the wild shows similar results with a 20–40% reduction in the time spent in compiling JavaScript code both on desktop and mobile. On Android, this optimization also translates to a 1–2% reduction in the top-level page-load metrics like the time a webpage takes to become interactive. We also monitored the memory and disk usage of Chrome and did not see any noticeable regressions.