V8 built-in functions (builtins) consume memory in every instance of V8. The builtin count, average size, and the number of V8 instances per Chrome browser tab have been growing significantly. This blog post describes how we reduced the median V8 heap size per website by 19% over the past year.

Background #

V8 ships with an extensive library of JavaScript (JS) built-in functions. Many builtins are directly exposed to JS developers as functions installed on JS built-in objects, such as RegExp.prototype.exec and Array.prototype.sort; other builtins implement various internal functionality. Machine code for builtins is generated by V8’s own compiler, and is loaded onto the managed heap state for every V8 Isolate upon initialization. An Isolate represents an isolated instance of the V8 engine, and every browser tab in Chrome contains at least one Isolate. Every Isolate has its own managed heap, and thus its own copy of all builtins.

Back in 2015, builtins were mostly implemented in self-hosted JS, native assembly, or in C++. They were fairly small, and creating a copy for every Isolate was less problematic.

Much has changed in this space over the last years.

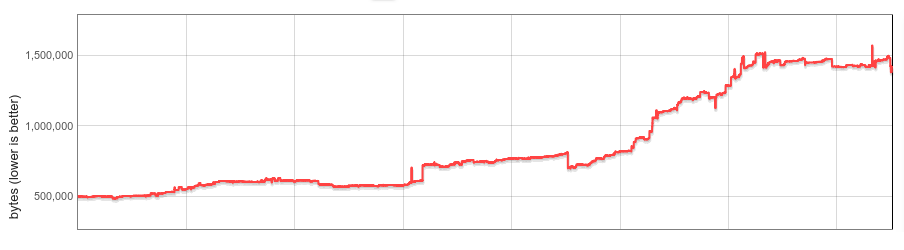

In 2016, V8 began experimenting with builtins implemented in CodeStubAssembler (CSA). This turned out to both be convenient (platform-independent, readable) and to produce efficient code, so CSA builtins became ubiquitous. For a variety of reasons, CSA builtins tend to produce larger code, and the size of V8 builtins roughly tripled as more and more were ported to CSA. By mid-2017, their per-Isolate overhead had grown significantly and we started thinking about a systematic solution. V8 snapshot size (including builtins) from 2015 until 2017

V8 snapshot size (including builtins) from 2015 until 2017

In late 2017, we implemented lazy builtin (and bytecode handler) deserialization as a first step. Our initial analysis showed that most sites used less than half of all builtins. With lazy deserialization, builtins are loaded on-demand, and unused builtins are never loaded into the Isolate. Lazy deserialization was shipped in Chrome 64 with promising memory savings. But: builtin memory overhead was still linear in the number of Isolates.

Then, Spectre was disclosed, and Chrome ultimately turned on site isolation to mitigate its effects. Site isolation limits a Chrome renderer process to documents from a single origin. Thus, with site isolation, many browsing tabs create more renderer processes and more V8 Isolates. Even though managing per-Isolate overhead has always been important, site isolation has made it even more so.

Embedded builtins #

Our goal for this project was to completely eliminate per-Isolate builtin overhead.

The idea behind it was simple. Conceptually, builtins are identical across Isolates, and are only bound to an Isolate because of implementation details. If we could make builtins truly isolate-independent, we could keep a single copy in memory and share them across all Isolates. And if we could make them process-independent, they could even be shared across processes.

In practice, we faced several challenges. Generated builtin code was neither isolate- nor process-independent due to embedded pointers to isolate- and process-specific data. V8 had no concept of executing generated code located outside the managed heap. Builtins had to be shared across processes, ideally by reusing existing OS mechanisms. And finally (this turned out to be the long tail), performance must not noticeably regress.

The following sections describe our solution in detail.

Isolate- and process-independent code #

Builtins are generated by V8’s compiler internal pipeline, which embeds references to heap constants (located on the Isolate’s managed heap), call targets (Code objects, also on the managed heap), and to isolate- and process-specific addresses (e.g.: C runtime functions or a pointer to the Isolate itself, also called ’external references’) directly into the code. In x64 assembly, a load of such an object could look as follows:

// Load an embedded address into register rbx.

REX.W movq rbx,0x56526afd0f70

V8 has a moving garbage collector, and the location of the target object could change over time. Should the target be moved during collection, the GC updates the generated code to point at the new location.

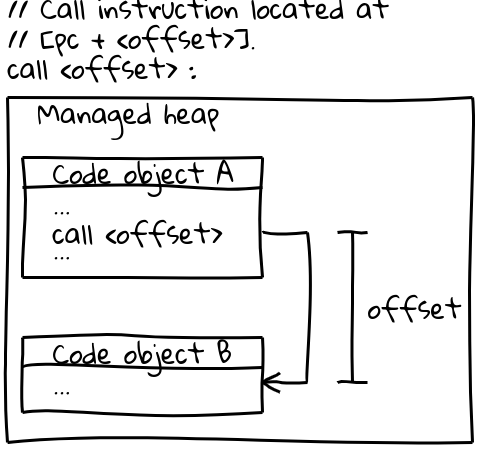

On x64 (and most other architectures), calls to other Code objects use an efficient call instruction which specifies the call target by an offset from the current program counter (an interesting detail: V8 reserves its entire CODE_SPACE on the managed heap at startup to ensure all possible Code objects remain within an addressable offset of each other). The relevant part of the calling sequence looks like this:

// Call instruction located at [pc + <offset>].

call <offset>

A pc-relative call

A pc-relative callCode objects themselves live on the managed heap and are movable. When they are moved, the GC updates the offset at all relevant call sites.

In order to share builtins across processes, generated code must be immutable as well as isolate- and process-independent. Both instruction sequences above do not fulfill that requirement: they directly embed addresses in the code, and are patched at runtime by the GC.

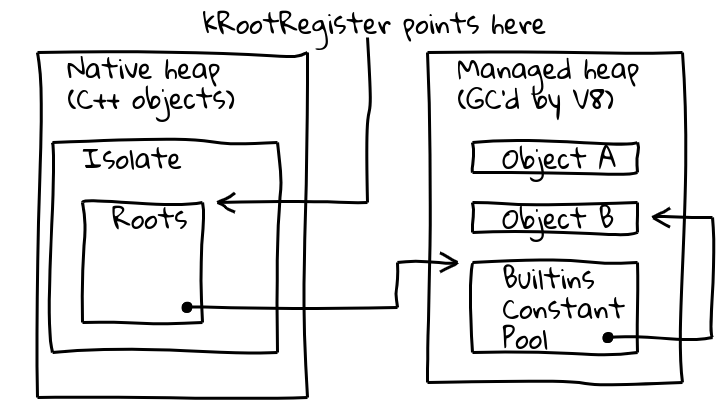

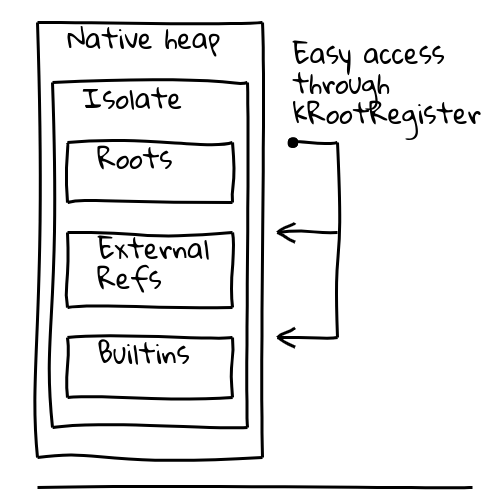

To address both issues, we introduced an indirection through a dedicated, so-called root register, which holds a pointer into a known location within the current Isolate. Isolate layout

Isolate layout

V8’s Isolate class contains the roots table, which itself contains pointers to root objects on the managed heap. The root register permanently holds the address of the roots table.

The new, isolate- and process-independent way to load a root object thus becomes:

// Load the constant address located at the given

// offset from roots.

REX.W movq rax,[kRootRegister + <offset>]

Root heap constants can be loaded directly from the roots list as above. Other heap constants use an additional indirection through a global builtins constant pool, itself stored on the roots list:

// Load the builtins constant pool, then the

// desired constant.

REX.W movq rax,[kRootRegister + <offset>]

REX.W movq rax,[rax + 0x1d7]

For Code targets, we initially switched to a more involved calling sequence which loads the target Code object from the global builtins constant pool as above, loads the target address into a register, and finally performs an indirect call.

With these changes, generated code became isolate- and process-independent and we could begin working on sharing it between processes.

Sharing across processes #

We initially evaluated two alternatives. Builtins could either be shared by mmap-ing a data blob file into memory; or, they could be embedded directly into the binary. We took the latter approach since it had the advantage that we would automatically reuse standard OS mechanisms to share memory across processes, and the change would not require additional logic by V8 embedders such as Chrome. We were confident in this approach since Dart’s AOT compilation had already successfully binary-embedded generated code.

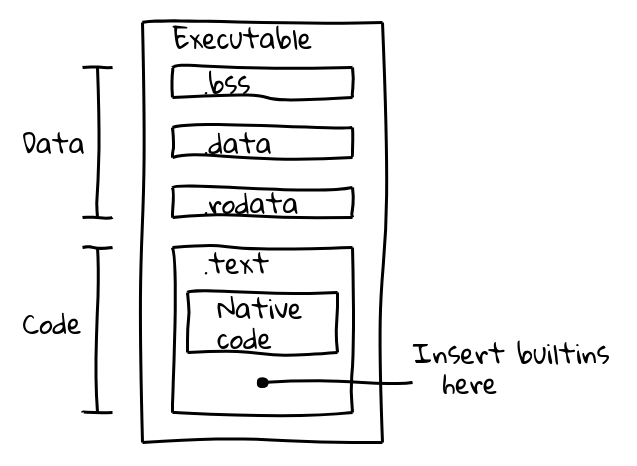

An executable binary file is split into several sections. For example, an ELF binary contains data in the .data (initialized data), .ro_data (initialized read-only data), and .bss (uninitialized data) sections, while native executable code is placed in .text. Our goal was to pack the builtins code into the .text section alongside native code. Sections of an executable binary file

Sections of an executable binary file

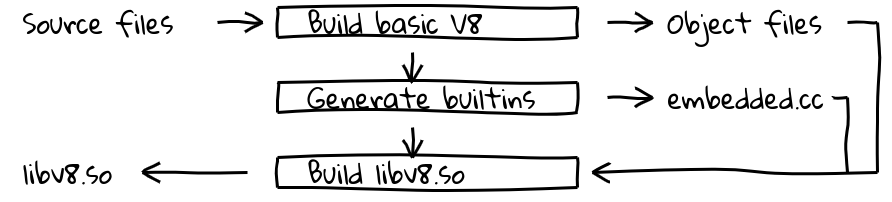

This was done by introducing a new build step that used V8’s internal compiler pipeline to generate native code for all builtins and output their contents in embedded.cc. This file is then compiled into the final V8 binary. The (simplified) V8 embedded build process

The (simplified) V8 embedded build process

The embedded.cc file itself contains both metadata and generated builtins machine code as a series of .byte directives that instruct the C++ compiler (in our case, clang or gcc) to place the specified byte sequence directly into the output object file (and later the executable).

// Information about embedded builtins are included in

// a metadata table.

V8_EMBEDDED_TEXT_HEADER(v8_Default_embedded_blob_)

__asm__(".byte 0x65,0x6d,0xcd,0x37,0xa8,0x1b,0x25,0x7e\n"

[snip metadata]

// Followed by the generated machine code.

__asm__(V8_ASM_LABEL("Builtins_RecordWrite"));

__asm__(".byte 0x55,0x48,0x89,0xe5,0x6a,0x18,0x48,0x83\n"

[snip builtins code]

Contents of the .text section are mapped into read-only executable memory at runtime, and the operating system will share memory across processes as long as it contains only position-independent code without relocatable symbols. This is exactly what we wanted.

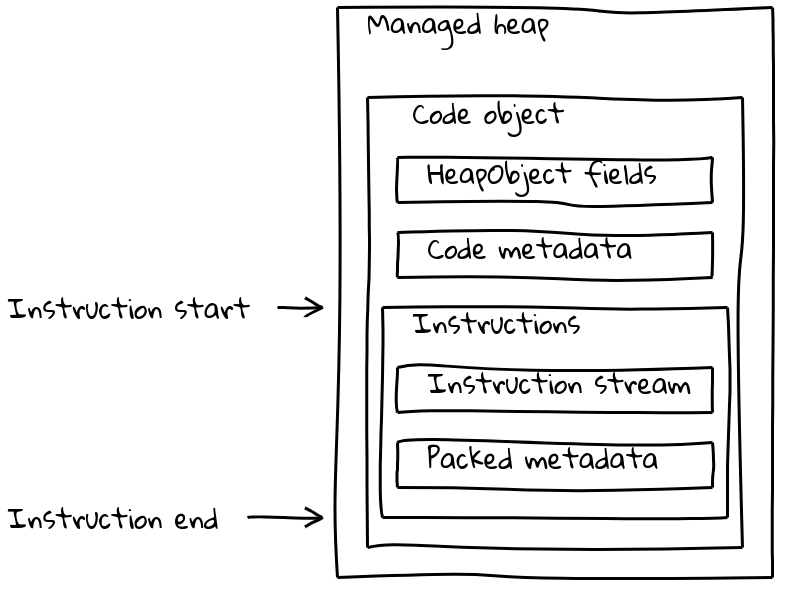

But V8’s Code objects consist not only of the instruction stream, but also have various pieces of (sometimes isolate-dependent) metadata. Normal run-of-the-mill Code objects pack both metadata and the instruction stream into a variable-sized Code object that is located on the managed heap. On-heap

On-heap Code object layout

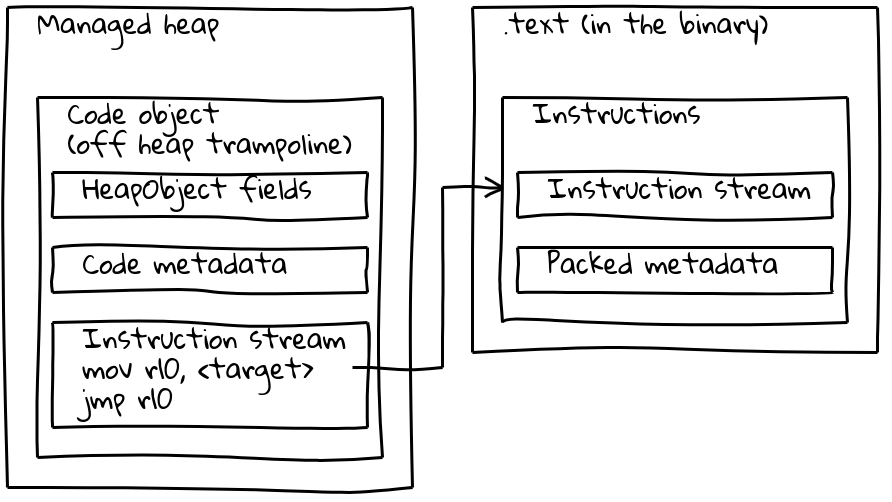

As we’ve seen, embedded builtins have their native instruction stream located outside the managed heap, embedded into the .text section. To preserve their metadata, each embedded builtin also has a small associated Code object on the managed heap, called the off-heap trampoline. Metadata is stored on the trampoline as for standard Code objects, while the inlined instruction stream simply contains a short sequence which loads the address of the embedded instructions and jumps there. Off-heap

Off-heap Code object layout

The trampoline allows V8 to handle all Code objects uniformly. For most purposes, it is irrelevant whether the given Code object refers to standard code on the managed heap or to an embedded builtin.

With the solution described in previous sections, embedded builtins were essentially feature-complete, but benchmarks showed that they came with significant slowdowns. For instance, our initial solution regressed Speedometer 2.0 by more than 5% overall.

We began to hunt for optimization opportunities, and identified major sources of slowdowns. The generated code was slower due to frequent indirections taken to access isolate- and process-dependent objects. Root constants were loaded from the root list (1 indirection), other heap constants from the global builtins constant pool (2 indirections), and external references additionally had to be unpacked from within a heap object (3 indirections). The worst offender was our new calling sequence, which had to load the trampoline Code object, call it, only to then jump to the target address. Finally, it appears that calls between the managed heap and binary-embedded code were inherently slower, possibly due to the long jump distance interfering with the CPU’s branch prediction.

Our work thus concentrated on 1. reducing indirections, and 2. improving the builtin calling sequence. To address the former, we altered the Isolate object layout to turn most object loads into a single root-relative load. The global builtins constant pool still exists, but only contains infrequently-accessed objects. Optimized Isolate layout

Optimized Isolate layout

Calling sequences were significantly improved on two fronts. Builtin-to-builtin calls were converted into a single pc-relative call instruction. This was not possible for runtime-generated JIT code since the pc-relative offset could exceed the maximal 32-bit value. There, we inlined the off-heap trampoline into all call sites, reducing the calling sequence from 6 to just 2 instructions.

With these optimizations, we were able to limit regressions on Speedometer 2.0 to roughly 0.5%.

Results #

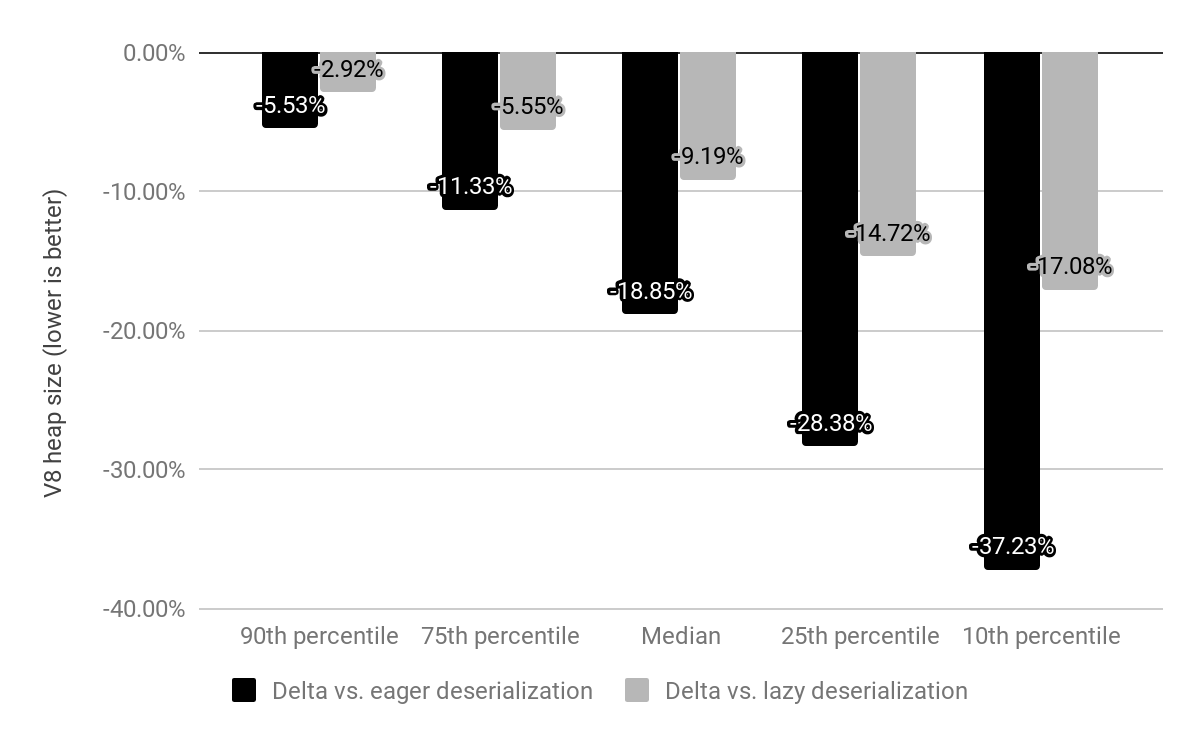

We evaluated the impact of embedded builtins on x64 over the top 10k most popular websites, and compared against both lazy- and eager deserialization (described above). V8 heap size reduction vs. eager and lazy deserialization

V8 heap size reduction vs. eager and lazy deserialization

Whereas previously Chrome would ship with a memory-mapped snapshot that we’d deserialize on each Isolate, now the snapshot is replaced by embedded builtins that are still memory mapped but do not need to be deserialized. The cost for builtins used to be c*(1 + n) where n is the number of Isolates and c the memory cost of all builtins, whereas now it’s just c * 1 (in practice, a small amount of per-Isolate overhead also remains for off heap trampolines).

Compared against eager deserialization, we reduced the median V8 heap size by 19%. The median Chrome renderer process size per site has decreased by 4%. In absolute numbers, the 50th percentile saves 1.9 MB, the 30th percentile saves 3.4 MB, and the 10th percentile saves 6.5 MB per site.

Significant additional memory savings are expected once bytecode handlers are also binary-embedded.

Embedded builtins are rolling out on x64 in Chrome 69, and mobile platforms will follow in Chrome 70. Support for ia32 is expected to be released in late 2018.

Note: All diagrams were generated using Vyacheslav Egorov’s awesome Shaky Diagramming tool.